In Britain, the summer of 2023 was a non-stop parade of indignity. A BBC presenter was exposed for possessing indecent images of children; a former Prime Minister was found guilty of misleading Parliament; a nurse was convicted of murdering seven babies. The front pages wrote themselves.

Meanwhile, in north Birmingham, away from the public eye, a silent killer was on the loose.

The first victim, a 38-year-old labourer, was found on 7 June after collapsing at home. The second was discovered a week later; the third and fourth, the week after that. By July, the deaths had become an almost daily occurrence. Eight bodies were found over the course of just 10 days — including two on the same evening, in the same building.

By the end of August, the death toll had risen to 21. Most of the victims had died in hostels or Houses of Multiple Occupation (HMOs). Each, inquests would later reveal, had been poisoned. The killer in question: a mysterious drug called a nitazene, a synthetic opioid up to 40 times more potent than fentanyl. “It’s like a little bomb going off in your brain,” says one user who survived.

One woman saw the nitazene wave coming. In 2009, Dr Judith Yates, a GP in Birmingham, started to maintain a database of every drug-related death in the city, after becoming frustrated at the lack of centralised data. “Nobody was paying me and there was no budget to do it,” she says now. Even after Dr Yates, now 74, retired in 2015, she continued to report any unusual findings from the coroner’s office to the local authorities. (Coroners' reports are publicly available.) But in 2023, her warnings about nitazenes — and the dangers of keeping their prevalence a secret — were largely ignored.

“The council is very averse to anybody outside of Birmingham knowing when there's trouble in the city,” she says. “I should have had the strength of conviction to just tell people. But I waited for them to make an announcement.”

By the time they did on 3 August, it was too late.

Britain considers opioids an American problem — a scourge of San Francisco, Baltimore and the former steel towns of Appalachia. In 2023 alone, fentanyl, the best-known synthetic opioid, killed 75,000 people in the US. But in our complacency, most Brits don’t realise we have an opioids crisis of our own.

Not that it’s entirely our fault. Unlike the US, the UK lacks a public overdose tracking dashboard (though one is being developed), and official statistics are widely considered a significant underestimate. For the most part, though, the Government is reluctant to publish any detailed data at all.

In January this year, the Home Office quietly revealed that, since June 2023, there have been at least 400 nitazene-related deaths in the UK. This came three months after it published another document, breaking down deaths by regions — South East, South West, North East, and so on. Yet when Dispatch sent a Freedom of Information request asking for a more specific geographical breakdown, the Home Office declined. The information, apparently, was “exempt from disclosure” due to “security matters”, because it concerned data being analysed by the National Crime Agency.

On the ground, this lack of transparency has real-world consequences — for doctors, politicians, frontline workers and even drug users, many of whom can only discuss the threat of synthetic opioids in anecdotal terms. With grim irony, the National Crime Agency is explicit about what this means: “There has never been a more dangerous time to take drugs.”

So, Dispatch took a different approach, sending FOI requests to every ambulance service in the UK to find out how many times Naloxone — a drug used to rapidly reverse an opioid overdose — had been administered in 2023 and 2024. We then converted this data to map on to the UK’s 360 local authorities.

The findings, as the below map illustrates, offer the most detailed picture yet of Britain’s opioid crisis: a menace that extends from Cornwall in the south to the Shetland Islands in the north.

We can see, for instance, that last year Birmingham’s local authority saw the most suspected opioid overdoses (720), followed by Glasgow (615), Leicester (507), West Northamptonshire (431) and Belfast (405). We can also spot regional hotspots, with opioid overdoses particularly prevalent in the Midlands and South West.

Moreover, as the table below reveals, the data shows a troubling trend: in most districts, particularly in England, opioid overdoses are rising. In 2024, most districts saw increases on 2023.

| Local authority district | Incidents in 2024 | Net change on 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Birmingham | 720 | +82 |

| 2. Glasgow City | 615 | -203 |

| 3. Leicester | 507 | +217 |

| 4. West Northamptonshire | 431 | +147 |

| 5. Belfast | 405 | -15 |

| 6. Edinburgh | 305 | -89 |

| 7. Liverpool | 302 | +80 |

| 8. Nottingham | 292 | -24 |

| 9. Leeds | 291 | +56 |

| 10. Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole | 290 | +120 |

As with other attempts to collect data on synthetic opioids, these findings are almost certainly an underestimate. They do not include instances where Naloxone — which is delivered via an injection or nasal spray — has been administered in hospitals, or on the street by police or support workers. And of course, they do not show where Naloxone hasn’t been used, or where opioid-overdose deaths have taken place. What this new information does provide, however, is a clearer indication of where opioids, and particularly nitazenes, are being taken — with Birmingham at the top.

But why was England’s second city the worst-hit?

When contacted by Dispatch, Change Grow Live, a publicly funded charity that provides drug services in Birmingham, declined to comment, while a spokesperson for the council pointed out that the city’s local authority is by far the largest in the UK, and therefore likely to have the most overdoses. (If Greater London’s boroughs were merged into one local authority, it would register almost four times as many incidents as Birmingham.)

But is Birmingham’s spike simply a matter of local authority size? According to Dr Yates, the impurity of the heroin sold in Birmingham may be a factor. “Looking at the toxicology reports here,” she says, “some of the fatal drugs didn't contain any heroin at all — just [super potent] nitazenes and paracetamol.” She also highlights the fact that 60% of Birmingham’s residents live in the three lowest levels of deprivation, where opioid usage is significantly more common.

Looking back at the summer of 2023, however, other institutional failures start to emerge. But to understand them, one needs to first understand the story of nitazenes.

In 2018, in an attempt to explain America's own opioid crisis, the author Andrew Sullivan wrote an essay for New York Magazine titled “The Poison We Pick”. At one point, he observed how a stash of fentanyl packed into the trunk of a single car contained enough poison to kill the entire combined population of New Jersey and New York. “That’s more potential death than a dirty bomb or a small nuke,” he wrote.

How do today’s nitazenes compare? If a trunk-load of fentanyl is the equivalent of a single nuclear weapon, a trunk-load of nitazenes is the equivalent of 40. Nitazenes are the strongest opioid ever created, with some compounds 500 times stronger than heroin. Where it normally takes a heroin overdose 20 minutes to cause respiratory depression and death, one nitazene grain too many can kill in just two minutes.

Nitazenes came to Britain in two waves. The first arrived in 2020, a year after Donald Trump, then serving his first term as US President, convinced the Chinese government to ban the manufacturing of illicit fentanyl, which underground Chinese labs had been exporting to the US. This left China’s chemists with two options. Some pivoted to selling fentanyl ingredients to Mexico’s drug cartels, who could then synthesise it themselves and smuggle it into the US. Others shifted their focus to developing new synthetic substances.

Chief among them were nitazenes, a class of synthetic opioid developed by a Swiss pharmaceutical company in the 1950s. At the time, with morphine stocks depleted after two world wars, scientists were desperate to find a replacement painkiller. But the nitazenes were found to cause fatal respiratory depression during trials, and were never approved for market.

However, this didn’t deter China’s underground chemists, who thought they’d struck gold with the cheap, easy-to-produce compound. The plan was to disguise nitazenes as two types of drugs known to reduce anxiety levels — Oxycodone (a semi-synthetic opioid) and Benzodiazepines — and sell them as pills on the dark web to unsuspecting users in America, Europe and the UK. It didn’t take long for the new drugs to claim their first victims.

During the lockdown of 2020, Will Melbourne, a 19-year-old diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, began struggling with anxiety and started buying Oxycodone on the dark web. In December, a nondescript envelope arrived at his flat in Cheshire. Inside was a pack of pills, each laced with metonitazene, a nitazene compound 50 times stronger than heroin. He died within seconds of taking one.

It is unknown how many people in the UK died after taking nitazenes during this first wave. A backlog of inquests had built up over the pandemic and coroners didn’t routinely test for nitazenes. But Dr Yates believes a disproportionate number were young men who thought they were buying anti-anxiety medication. “They were mostly disguised as Oxycodone, Xanax and Benzodiazepines,” she says. After combing through Birmingham’s coroners’ records, she found that at least three men — all under 28 — died in the city between October 2021 and January 2022 from nitazene overdoses.

“Taking these drugs is like playing Russian roulette,” John, Will Melbourne’s father, would later say.

If Britain’s first wave of nitazenes was made in China, its second was sparked in Afghanistan. Since the 1950s, the world’s heroin trade has depended on poppies cultivated in Afghanistan’s Helmand, Farah and Nimroz provinces. But after the Taliban recaptured the country in 2021, and banned opium cultivation the following year, the industry collapsed. Within a year, poppy cultivation in Helmand Province had plummeted by 99%, with other regions soon following suit.

While this hasn’t caused a complete heroin shortage, because previous stockpiles remain, it has had a dramatic effect on heroin purity in the UK. And to compensate for this weaker supply, dealers now often cut heroin with nitazenes. In Birmingham, the fatal repercussions of this became clear during that fateful summer of 2023.

How the nitazenes were smuggled into Birmingham is still unknown, but frontline officials — who Dispatch is keeping anonymous — offered a plausible scenario. In May or June, a dealer likely imported from China a tiny batch — perhaps just enough to fit in an envelope — of n-desethyl isotonitazene, a nitazene 20 times more potent than fentanyl. As an experiment, to see if it could pass for heroin, they then sprinkled a few granules into tiny bags of low-purity heroin, paracetamol and caffeine for users to inject, snort or smoke. Throughout June and July, these deadly samples were then sold in a sweeping arc across Birmingham’s northern districts — Lozells, Handsworth and Aston — where many users lived in homeless hostels or HMOs.

Officially, 21 people died that summer, while at least 19 others were hospitalised with non-fatal overdoses. An inquest later heard that one female victim had referred herself to a local charity just hours before fatally overdosing, saying that “her life was going nowhere”. That same night, in the same hostel, another man was found dead on his bedroom floor. Both had taken the same drug.

In mid-July, just as Birmingham’s surge of nitazene deaths was peaking, the authorities made two startling decisions. The first came from Craig Guildford, Chief Constable of West Midlands Police, who ruled that officers should stop carrying Naloxone despite the wave of overdoses. He wanted to review its use and design “a robust plan for its expansion force-wide”.

“It was the worst possible timing,” says Dr Yates. “It's mind-boggling.” When I asked West Midlands Police if Guildford regretted the decision, they refused to answer, instead claiming that much of their existing stock had expired. The force reversed its stance six months later, after the review was complete. By that point, 37 people had died in Birmingham following nitazene overdoses.

The second questionable decision was taken by Birmingham City Council’s Public Health division, which was reluctant to immediately publicise the nitazene deaths. Instead, the council sent emails and Naloxone kits to the owners of HMOs and hostels where vulnerable people might be staying. But there was no public awareness campaign, which might have alerted the supplier (or suppliers) to the fact that their drugs were killing customers.

The first press release was published on 3 August, by which point at least 16 people had died, and many more had overdosed. “Whenever I said we should go public, I would get my wrists slapped,” Dr Yates adds. “It needed to be in the public domain so that the people who were buying pills would know what was happening.”

Dr Yates contrasts this silence with the swift action taken in Dublin in November 2023, when nitazenes caused 57 overdoses in four days. “Almost immediately, they put up warning signs next to roads and handed out flyers to homeless opioid users. Why couldn’t we have done that?”

When I posed this question to Birmingham City Council, they maintained they “wanted to avoid stigmatising vulnerable groups in our city, and instead encourage meaningful conversations around drug harm reduction and, crucially, enable users to be able to access the information, support and treatment they required.”

But is this the entire story?

On 5 September 2023, with nitazenes still tearing through north Birmingham, the council issued a Section 114 notice — effectively declaring itself bankrupt. In other words, just as Birmingham was gripped by an opioid epidemic, its council ran out of money. In February this year, it confirmed plans to cut £148 million from its budget, including £43 million from adult social care. And this, just two years after a government-commissioned review warned that funding cuts had already “left [drug] treatment and recovery services on their knees”. Even so, a spokesperson maintained that “the Section 114 notice was not a factor” in the council’s delayed response.

Where does this leave Birmingham today? In January this year, the Government announced further bans on synthetic opioids and claimed that Border Force dogs were being trained to detect nitazenes. But in Birmingham, these measures have yet to make an impact.

When I visited last week, the city was still coming to terms with an ongoing bin strike, which had just been declared a “major incident” by the council. Putrefying piles of rubbish dotted the streets, some six feet tall. Meanwhile, outside of the HMOs where people died in 2023, new residents described how overdoses were becoming more frequent. “You can’t move for rats and needles,” said one. Another added: “I don’t do drugs but you can see why people do.”

Still, perhaps the greatest toll of Britain’s hidden opioid crisis is on those it leaves behind: on the families of the anxious teenagers who unwittingly bought nitazenes in the first wave — and on the families of the vulnerable and homeless who were sold poisoned heroin in the second.

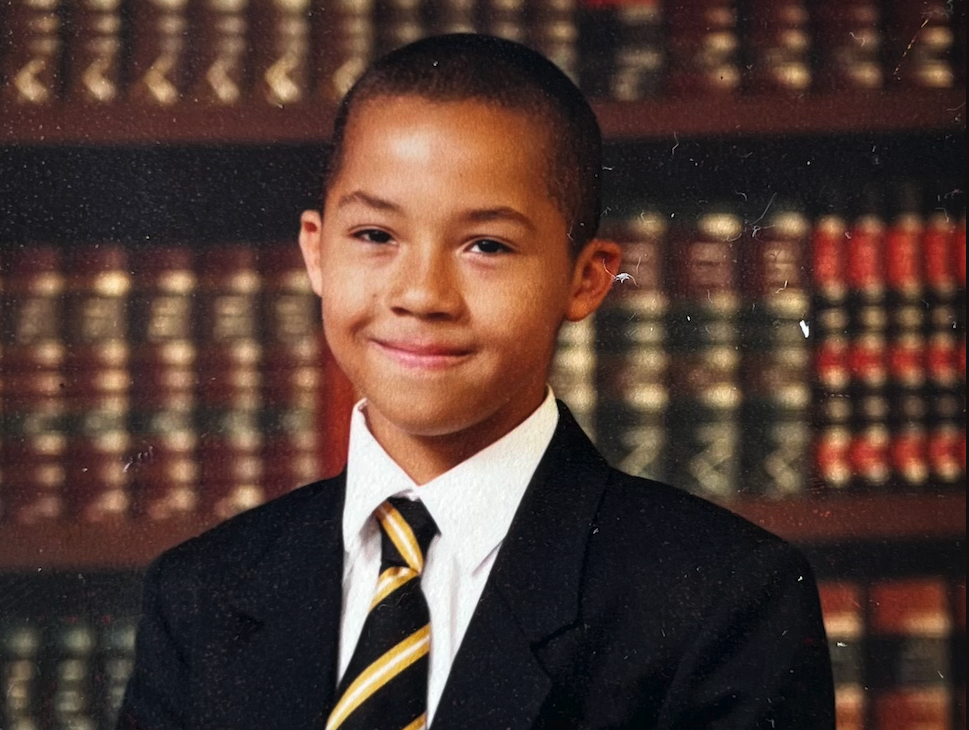

Simeon McAnoy, 33, was one of those who died in 2023. Pushed into a life of petty crime and incarceration as a teenager, he started taking heroin after his release — until one day in October, he injected a dose laced with n-desethyl isotonitazene.

His mother Jackie still visits his grave twice a day. “I don’t understand how the nitazenes weren’t picked up at the start,” she tells me. “There were no warnings… He didn’t stand a chance."