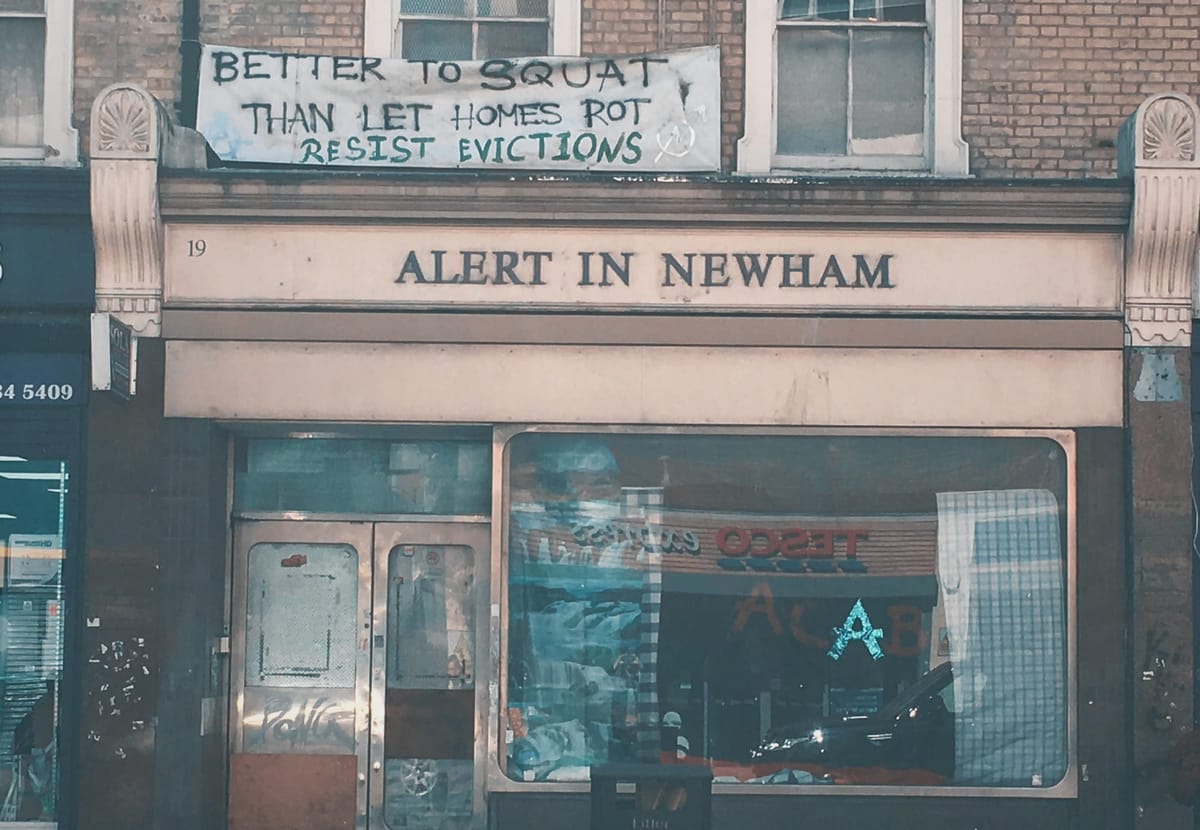

Oz had just received word they were going to be evicted. But judging by the banner hanging outside, the crew were intending to take a stand: BETTER TO SQUAT THAN LET HOMES ROT. RESIST EVICTIONS.

The shop shutter had been repaired, but it wouldn’t be strong enough to keep the bailiffs out, so a plan was hatched: use Sitex Security Screens to fortify the space. These metal sheets, a familiar sight across London, are usually deployed to keep squatters out of empty properties. Oz’s idea was to turn that technology back on itself.

After hearing that a squat around the corner had managed to prise every Sitex sheet from their building, a shopping trolley was dispatched, loaded up and pushed back down the road in broad daylight. The panels flapped on either side, nearly clipping the ground whenever a wheel hit a kerb or a pothole. A driver in a flashy German car stopped and waved the trolley across the road. He might have been a landlord, an estate agent, a solicitor, or just another intermediary in London’s vast financial sector. Yet here he was, making way for barricade materials bound for a squat.

The squat itself was a long-abandoned charity shop on Forest Gate high street. Downstairs, it was classic squat territory: bikes at various stages of repair, old sofas, office chairs, and other salvage liberated from skips and bins. Upstairs, the former offices had been turned into bedrooms — with the bonus of a working toilet.

You might think you already know what squatting is, or the kind of people who do it. But our ideas about squatters have been shaped by long-running and curated stereotypes that paint them as layabouts, political extremists, parasites. They are portrayed as a direct threat to the imagined “law-abiding, hard-working majority”, because they are seen as taking something that isn’t “rightfully” theirs.

Register for free to read this article.