On a grizzly Good Friday in The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, it rained for the first time in weeks. The fetid mounds of rubbish which had blighted the area had mostly been cleared away, and, in the pubs at least, there was cause for celebration.

But just up the road from the city centre, the atmosphere was strained. Officially, nothing was due to happen at the town hall that evening. Ticket holders like me were only emailed the location the night before. By 4pm, the car park was beginning to fill. A faded auto-sleeper RV was parked directly beside the entrance, a large Route 66 sticker emblazoned on one side. Above it, a luminous label declared: “Lighting the fire for freedom.”

I was in the right place.

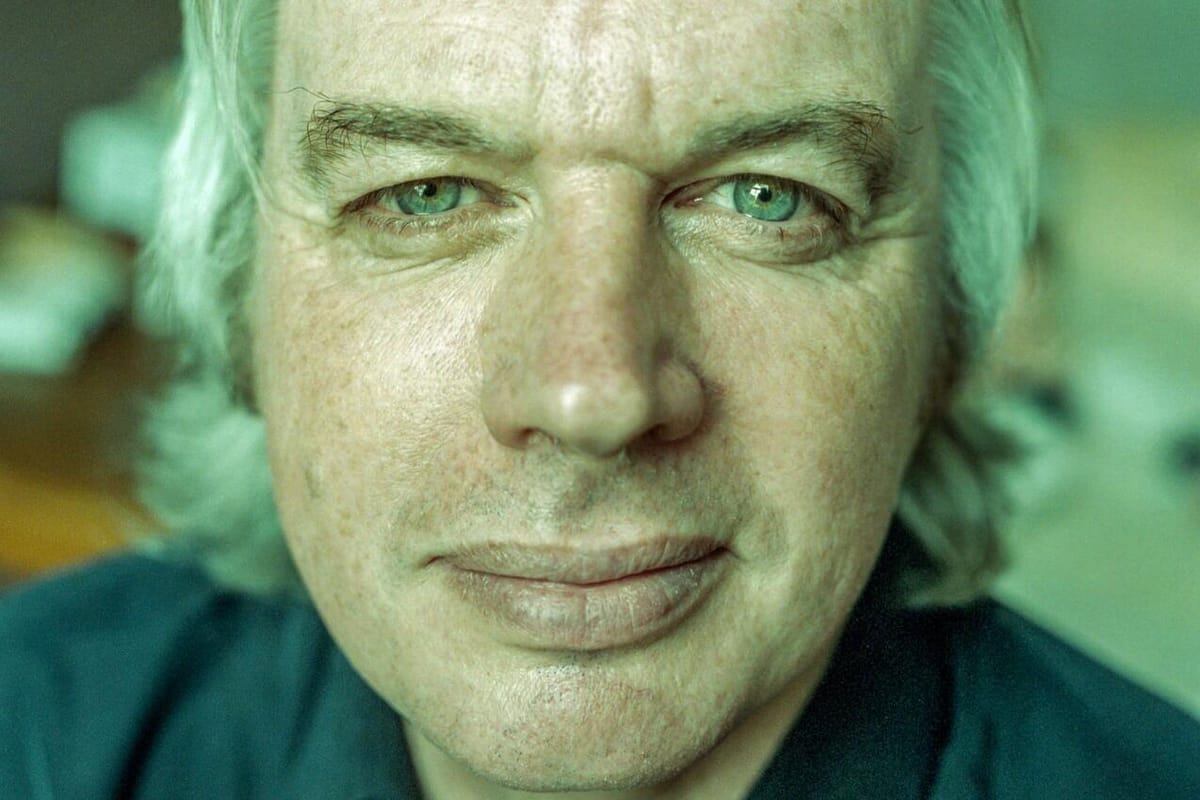

Like a lot of people, I was only loosely aware of David Icke before the pandemic. I knew him as the charismatic conspiracist who claimed the world was ruled by shape-shifting extraterrestrial lizards — the former footballer and sports broadcaster who drew huge crowds in the 1990s and early 2000s after declaring himself the Son of God on Wogan in 1991. But by the late 2010s, he had mostly faded from view.

Then, in 2020, Icke became a pariah. He claimed that the “global cult” was spreading the symptoms of disease through fake vaccines and 5G phone networks, and emerged as a figurehead in the anti-vaccine movement. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube removed him from their platforms. In 2022, the Dutch government barred him from entering the country on the grounds that his presence posed a threat to the public order — a ban which automatically applied to the wider Schengen Area and was extended indefinitely last year.

Icke is not, generally speaking, a great believer in coincidence. But as it happened, his youngest son Jaymie — now 32 — launched the Ickonic Media Group in October 2019: a Netflix-style “alternative” streaming platform where, for £12.99 a month, subscribers could access Icke’s back-catalogue of live shows alongside a heady mix of podcasts and documentaries questioning “mainstream” narratives. It was perfect timing. Just as governments around the world began imposing Covid restrictions, Ickonic was ready to serve up content to an audience disenchanted with traditional platforms.

While Icke, now 73, still publishes a book every year or so and occasionally goes on tour, it’s his sons who are steering Ickonic in a new direction. Icke isn’t even listed as a director in the company records. Instead, his eldest, Gareth, 43 — a former beach footballer — now hosts a dizzying array of podcasts and current affairs segments on the platform, alongside a growing cast of “alternative” filmmakers, writers and TV personalities. Recent videos cover the Iberian power outage, Virginia Giuffre's death and the threat of smart meters.

I’d come to Birmingham for the second of Ickonic’s live shows: a panel discussion with an audience Q&A. I was curious to see who was drawn to these events — and to understand why, after so much controversy, Icke’s theories still hold such sway. Sitting in a self-consciously trendy cafe in London, flicking through his “Dot connector” news programmes, it felt like peering into a parallel universe. I parted with £37 and booked my ticket.

Outside the venue, an hour before doors open at 6pm, the queue is already snaking along the pavement. I get chatting to a couple of old-timers — two relaxed blokes in their 50s, both in hiking gear. They’re school friends, now brothers-in-law after Tom* married Paul’s sister. “I’ve been into Icke since the 1990s,” Tom tells me. “Ever since Wogan, really.”

During that much-ridiculed TV appearance, Icke predicted that cataclysmic weather events would befall the planet and claimed that Saddam Hussein was, despite appearances, dead. For Tom, though, it was “the state of the world stuff” that resonated. “When a child dies of preventable disease every two seconds,” said Icke, “when the economic system must destroy the earth simply for that system to survive, when you see all the wars and all the pain and suffering — is it a force of love and wisdom and tolerance that is in control of this planet? Or is it a force that wishes to bring pain and suffering?”

Seven years later, in his book The Biggest Secret: The Book That Will Change the World, Icke gave that “force” a form: a race of bipedal, extraterrestrial reptilians who feed off negative human emotions.

Are they fully on board with that?

“I’m open to it, yeah,” says Tom.

“They walked the earth and slept with the daughters of men,” Paul replies. “Then they went underground.”

With that, we go inside.

Our home for the evening is the Vesey Ballroom: an ornate theatre hall with elegant golden chandeliers and rows of royal burgundy chairs. The adjoining conference room doesn’t offer merchandise, but there is a stall selling tea and chocolate buttons — the queue for which easily outdoes the bar.

Register for free to read this article.