"I protest!"

Renaud Camus is a portrait of theatrical indignation. His eyes widen; a wry smile tugs at his lips. “There is no such thing as the Great Replacement Theory. It’s not a theory at all!” To him, the Great Replacement is a fact — and the mere suggestion otherwise is a provocation.

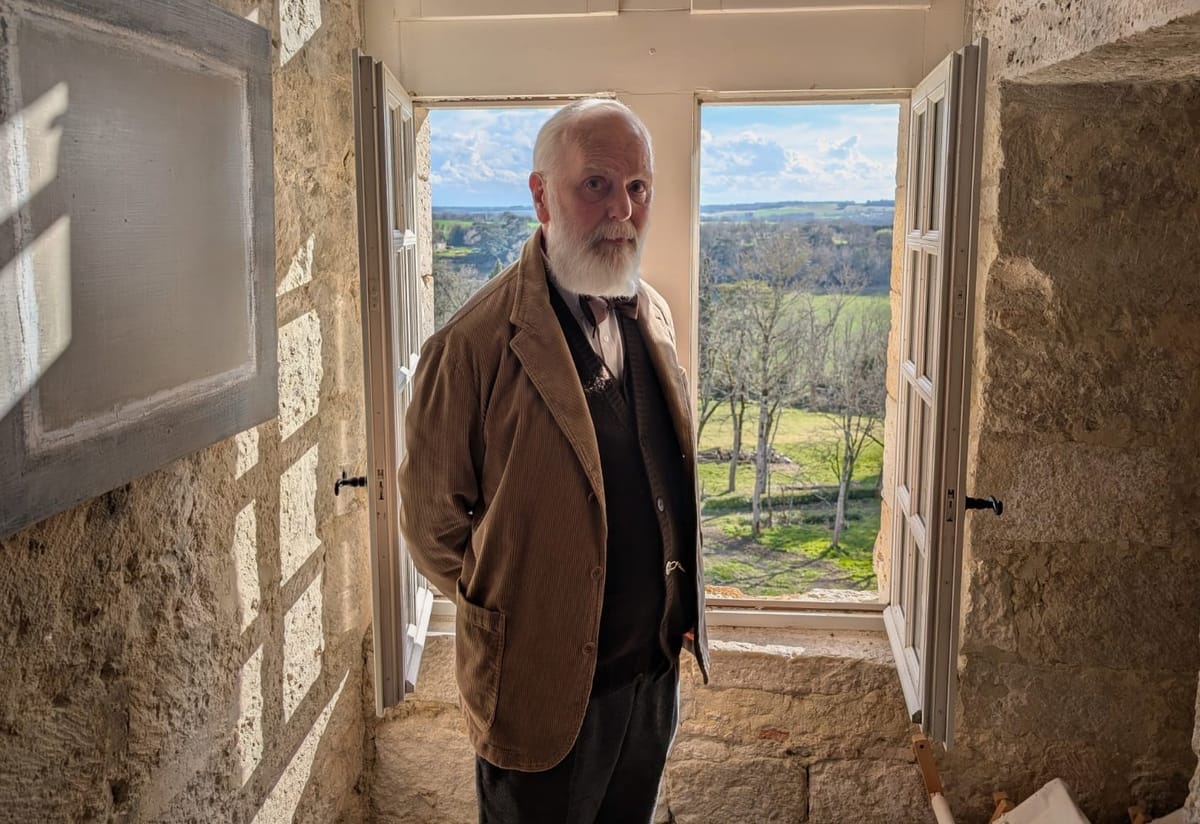

From the tower of his 14th-century castle, perched high on one of Gascony’s rolling hills, Camus claims he has seen the future of the West. It is, he warns, a future of replacement — a slow erasure of Europe’s “native” populations through mass immigration. The result is no less than “genocide by substitution”.

For his troubles, Camus now lives in a kind of exile. Once an essayist of minor renown, he is now one of Europe’s most contentious intellectuals — so much so that the UK Home Office just banned him from entering the country.

To his critics, Camus — no relation to the existentialist Albert — is the architect of a pernicious conspiracy theory: the belief that liberal governments are plotting to replace white populations with migrants. Some advocates claim this is intended to secure permanent left-wing majorities; others, such as right-wing provocateur Tommy Robinson, suggest the aim is to dismantle nation states and create a one-world government.

Camus’s critics point to the violent consequences of these theories. In New Zealand in 2019, and in the US in 2022, mass shooters cited Camus’s work in their manifestos. Fifty-one Muslims were murdered in the former, ten African-Americans in the latter. To many, this is proof that Camus is not simply a reactionary thinker, but a “dangerous” one.

Among some conservatives, however, such labels are ungenerous. Camus, they argue, is eccentric — but frequently misunderstood. “While Camus can be blunt,” writes Douglas Murray, “his thinking can also be subtle.” He is required reading for “anyone thinking seriously about long-term human sustainability”, says Mary Harrington. For Rod Dreher, Camus is “an honest man who refuses to be silent in the face of civilisational suicide”.

Now, that view is being tested once more. This Saturday, Camus was due to speak at a nationalist conference in the UK, hosted by the far-right Homeland Party. But last week, the Home Office banned him from entering the country. His presence, it said, was “not considered to be conducive to the public good”.

The decision has sparked renewed debate and drawn fresh attention to Camus's ideas. So, how dangerous is he? Last month, I travelled to France to find out.

If, as Renaud Camus believes, the Great Replacement is the most pressing issue of our time, it has yet to trouble Plieux. An hour north-west of Toulouse, the village lies in a state of pastoral slumber. Light blue shutters shield nearly every window. Despite its picturesque church and scattering of tiny boutiques, Tripadvisor lists just one attraction: the Château de Plieux.

Camus, now 78, bought the fortified castle, with its ten-storey tower, in 1992. For much of his adult life, he was the very image of a Left Bank liberal. Disinherited by his parents after coming out as gay, he moved to Paris and marched in 1968 in support of progressive values. He joined the Socialist Party, moved in rarefied literary circles, and cultivated friendships with Roland Barthes, Andy Warhol and many more. Barthes even wrote the preface to Tricks, Camus’s semi-autobiographical novel — a candid catalogue of his sexual encounters in France and the US, where he had taught literature during the 1960s. (“He came the moment one of my fingers was pressed inside the crack of his ass,” reads one typical passage.) No less than Allen Ginsberg described Camus’s world as that of a “new urban homosexual, at ease in half a dozen countries”.

But that was another Camus. In his mid-forties, he left the city behind. “I’m claustrophobic, and I needed room for my books,” he tells me. With the proceeds from the sale of his Parisian apartment, he purchased the Château de Plieux and restored it, partly with government funds. In return, he was required to open the castle to the public for part of the year, though he stopped doing so during the Covid pandemic — and never resumed.

Freed from the expectations of Parisian life, Camus became increasingly reactionary. In 2001, he was accused of antisemitism after remarking on the number of Jewish critics on a regular panel on a public radio channel. In 2010, he gave a speech in which he referred to Muslims as “the armed wing of a group intent on conquering French territory”, and was later convicted of incitement to hatred.

In another speech in the same year — later published as Le Grand Remplacement in 2011 — Camus introduced France to his notion of “replacism”, a process that lulls native populations into complacency as they are quietly displaced. The result, he wrote, is that “one sees one people, takes a nap, and there’s another or several other peoples”. In 2020, he received a two-month suspended prison sentence for describing mass immigration as an “invasion”.

As his focus shifted from the literary Left to the identitarian Right, Camus was cast out of intellectual society. A few faltering attempts to launch his own political party came to nothing. Back in Plieux, he pulled up the drawbridge.

To this day, the castle’s defensive positions are nearly impossible to breach. When I arrive, I have to circle the perimeter — no bell, no intercom — until I stumble across a heavy door around the back. Several minutes after I knock, it creaks open. A man in a dark suit and spectacles stands before me. This is Pierre, Camus’s partner of 25 years. He leads me up a narrow spiral staircase, and leaves me in a vaulted antechamber lined with ageing books and oil portraits.

“Let me check if the Monsieur is ready for you,” Pierre says, and disappears.

The Monsieur rises as I enter his study — a vast stone hall draped in silence and books. At its far end an iMac dominates a large wooden desk, the only trace that we are still in the 21st century. Camus looks as if conjured from the pages of an academic novel: corduroy jacket, bow tie, clipped white beard. In the five minutes before we sit, he cites Nabokov, Racine and Flaubert.

Given that Camus's defenders so often insist he’s misunderstood, I begin by asking him to define the Great Replacement Theory.

After objecting to the term “theory”, he explains: “The Great Replacement is the change of people and the change of civilisation it implies. You have one people who, in one generation, turns into several people.”

Camus traces his first “observation” to 1999, when he was writing a tourist guide for the Hérault region in southern France. “I was in these very old villages, and suddenly I was only seeing women in veils,” he says. “I had seen them in the suburbs, but [not] in these villages.” Camus calls this a “terrible crime”. “Changing the culture is one of the worst things you can do,” he adds.

He outlines why in an essay on what he calls “Nocence” (his term for social and moral harm): “Every time a native is commanded to lower his gaze and step off the sidewalk, a little bit more of the country’s independence and its people’s freedom is dragged through the gutter.” Yet for Camus, the greater tragedy is our inability to even discuss such subjects. In a provocative essay titled The Second Career of Adolf Hitler, he suggests this is because Western democracies remain paralysed by the historical shame of the Holocaust. “Hitler the ghost,” he concludes, “has had an even greater effect than did Hitler the Führer.”

Surely such rhetoric downplays the horrors of Hitler’s actions? “I can hardly be accused of undermining the gravity of Hitler’s crimes,” Camus replies. (Later in our conversation, however, he claims Queen Elizabeth II's “silence” over the Great Replacement was “more criminal than the silence of Pope Pius”, who refused to condemn Nazi Germany during the Second World War.)

“I’m not saying the Great Replacement is as criminal [as the Holocaust],” Camus adds unconvincingly. “But you can compare the vastitude of the geopolitical consequences. I think the Europeans are destroyed as a civilisation and a culture.”

For Camus, the value of that culture hinges on a particular principle: the right to discriminate. “I love discrimination,” he says, with the air of a sommelier describing his favourite vintage. “Discrimination is one of the foundations of thinking in modern life.”

Should we discriminate between people?

“We must discriminate about everything,” he replies.

Even between races?

He nods.

Does that make him a racist?

“Yes,” he says, after a pause.

Camus then attempts to clarify.

“I think the term ‘anti-racist’ has totally changed its meaning — and the term racist should change in symmetry,” he says. In response, I suggest that while the meaning of anti-racism may have shifted, at its core, it still holds that people should not be judged or treated differently because of their race. Camus rejects the premise. “But it doesn’t mean that now,” he insists. “I think it is anti-racism that is genocidal now.”

At this point, the tone of the conversation tips again — and becomes more hostile. I ask whether, by identifying as a racist, he worries about giving intellectual cover to those who act on such beliefs. After all, references to “the Great Replacement” have appeared in multiple extremist manifestos. Given what happened in New Zealand, for instance, does he not feel the need to speak more carefully?

Register for free to read this article.