A century ago this month, on 13 October 1925, Margaret Roberts was born above a grocer’s shop in Grantham, Lincolnshire. She died as Baroness Thatcher in a suite at The Ritz in London 87 years later.

In the weeks ahead, much will be written about the Britain she left behind. But Britain is not one story. Its places, and its people, bear her legacy in different ways.

Over the past fortnight, I travelled across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to meet those who lived on the front lines of Thatcher’s Britain — and to see how their communities fare today.

I spoke with an IRA bomber, a Scottish miner who toasted her death, a rioter in Toxteth and others whose lives and memories represent Britain past and present.

You can read their stories below.

The Bomber (Co. Down)

“I’m not a rough and tough IRA man,” Colm insists, and he has the online reviews to prove it. His farmhouse boasts a 4.98 rating on Airbnb. “Colm is living history,” writes Jennifer from Wisconsin. “If you want to understand Ireland, he is the man to talk to,” adds Amy from California.

She may be right.

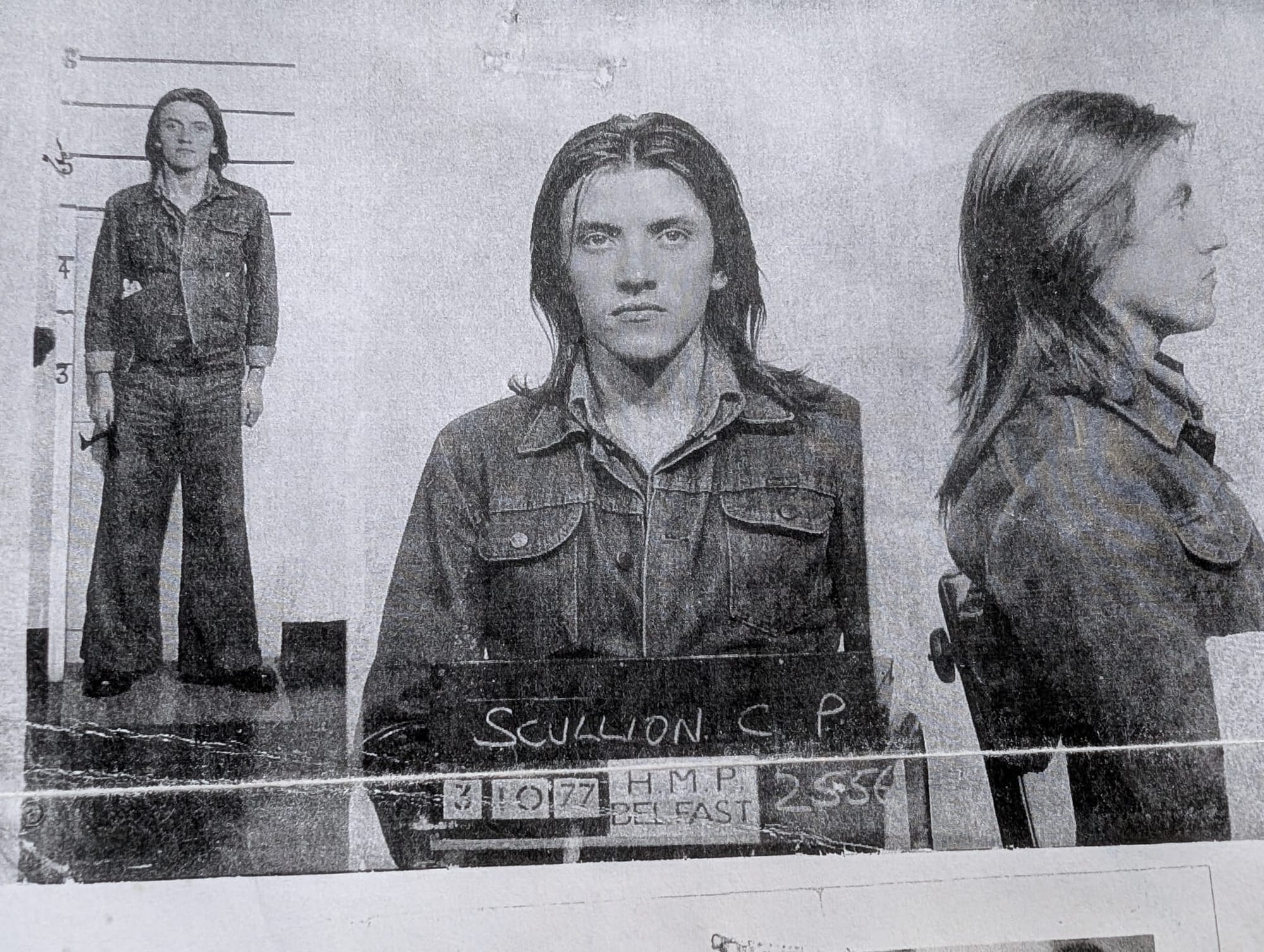

In the village of Bellaghy, County Derry, everyone has a Troubles story, but few have as many as Colm Scullion, 68. Bomber, blanketman, cellmate of Bobby Sands — quite a résumé for the gentle figure pouring tea across the table. These days, Colm caters to American tourists and spends afternoons at a nearby arts centre named after Seamus Heaney. His greatest nemesis now is the ticket machine at Belfast train station: “It’s a nightmare getting one and finding the platform.”

Through a hedge, up a winding track and inside Colm’s house, memories of past battles hint at a more turbulent life. There’s the signed poem by Gerry Adams on the wall, the photographs of fallen comrades, the slight limp that follows him from room to room. The latter was gifted by a blast that hurled him out of a car and into a hunger strike that would shake Thatcher’s government and the Union itself.

A bookish teenager with dreams of studying archaeology, Colm was accepted into the IRA aged 16. “We looked around us and saw unemployment and discrimination,” he recalls, when I ask why he joined. “In Derry, people were marching for something as basic as one man, one vote.” There was also a run-in with the British Army: on the way to a local dance, he was pinned to the floor by a rifle shoved down his throat. “Peaceful protest was tried,” he says, “but it didn’t work.”

Colm was sent for “basic training” and returned a bombmaker. He won’t speak on the record about his “missions”, except for the one that landed him in hospital, then prison. He had just parked up in Ballymena, a predominantly Protestant town, when a bomb went off prematurely. He doesn’t remember whether the flash or a bang came first, only the impact. “I think about that explosion every day. I had another bomb between my legs and one beside me.” They didn’t detonate.

There were two others in the car with him that day, including Thomas McElwee, who would later die on hunger strike. When Colm finally stumbled out of the car, he had a hole in his thigh and several toes missing.

From hospital he was taken to Crumlin Road prison, where Bobby Sands, who had been arrested for weapons possession, was the Officer Commanding (OC) who “debriefed” him. “We became friends right then.” Soon after, both men were attacked by Loyalist prisoners and ended up in the same ambulance.

In 1977, Colm — “Skull” to his comrades — was sentenced and sent to the notorious H-Blocks of the Maze: “a living hell” where IRA prisoners refused uniforms, instead choosing to wear blankets in protest at the removal of their political status. Later came the “no-wash” protest, and the hunger strikes of 1981.

Cells held two men — “four steps by four and a half” — and Colm was paired with Sands. “The first day he arrived, he refused to speak in English,” Colm recalls. Sands insisted on Irish, partly to keep guards from listening, partly to keep the language alive. “To be honest, I wasn’t very good,” Colm admits. “But what little Irish I had grew fast.”

Evenings were spent whispering down the wing in Irish: news from illicit radios, plans for the next protest. It was during these conversations that Sands proposed a second hunger strike, after another was called off earlier that year. A list was drawn up of those who would see it through to the death. Colm’s name wasn’t on it. “I just hadn’t the balls to do it,” he says. “We all agreed the injured couldn’t go on it — but that sounds like an excuse. I just couldn’t face death. Bobby and Frank Hughes [who also died on the hunger strike] were never going to back down.”

In his last letter home before the strike, Sands wrote that he believed he would die. Colm didn’t — especially not when Sands, after 41 days on strike and in prison hospital, was elected to Parliament in the Fermanagh and South Tyrone by-election.

Soon after Sands died, after 66 days on strike, Colm was released and rejoined the IRA. “I never got caught again,” he says, refusing to reveal how many bombs he planted and whether, and how many, people were killed. He regrets little. A united Ireland, he believes, will come in his children’s lifetime. “I’m just proud to have played a minuscule role in the movement and the struggle.”

During that struggle, he claims to have celebrated only two deaths. The first was in 1985, when the IRA executed Patrick Kerr, an off-duty prison officer who Colm claims “would personally beat” him and those on his wing.

The second was in 2013, when Margaret Thatcher died of a stroke. “Even outside the Irish context, we loathed her,” he says. “Her treatment of the miners, her friendship with Pinochet, the Belgrano. How she treated her own people was despicable.”

Then he softens. He talks of extending the hand of friendship to the Unionist community. He mentions close Protestant friends. And he describes his guests — Americans eager for stories, who leave glowing reviews. “I love the Airbnb,” he says, smiling. “You should check out the comments.”

The Miner (Danderhall, Scotland)

On 17 April 2013, as Margaret Thatcher’s funeral procession wound its way to St Paul’s Cathedral, the former miners of Monktonhall Colliery gathered at the village graveyard. As the rain lashed down, they laid four wreaths for the ten local men killed underground since the ‘60s. Then came whisky from silver hip flasks and a stream of morbid jokes. “Maggie’s in hell and she’s shut down three furnaces already,” one said.

Soaked through, they squelched back to the Danderhall Miners’ Club, seven miles south-east of Edinburgh. It was time for a party. Country and western ricocheted through the hall; by midnight, 300 people had come through the doors.

Hello! Sorry to interrupt.

To read the rest of this article, you’ll need to become a paid member. Stories like this demand weeks of reporting, writing and editing — and reader subscriptions are what make that possible.

If you believe in what Dispatch is doing, consider joining today with 75% off three months — that’s less than £2 a month.

And if that’s still too much, get in touch. We don't want to exclude anyone.

“It was all very organised,” recalls Paddy Duggan, a former engineer at Monktonhall Colliery. “We let the journalists in early to look around at the start. That was it. When they tried to come back later, when everyone was drunk, we turned them away. The party was for us — about solidarity, and about paying our respects to those who’d died.”

Tam Bennett was 22 during the Miners’ Strike of 1984, and was one of 4,400 men who lost their jobs at the pits of Monktonhall and nearby Bilston Glen. Now 66 and weakened by a recent stroke, he struggles to form full sentences. Still, when Thatcher’s name is mentioned, he delivers his verdict like gunfire: “Fuck her.”